Stationary Waves

A stationary wave is formed when two progressive waves that are travelling in opposite directions collide. The resulting wave still oscillates, but it doesn't transfer energy along the length of the wave. The particles are simply displaced from their equilibrium position.

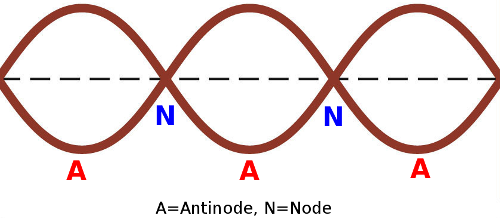

A stationary, or standing, wave forms a series of oscillating loops called antinodes, which are separated by nodes. These nodes are fixed and don't move at all.

Stationary waves can be transverse or longitudinal. String instruments set up transverse standing waves in the string, whereas wind instruments set up a longitudinal standing wave in a column of air.

One important thing to remember is that progressive waves can reflect off a fixed point, for example the clamped end of a string, back onto themselves. This results in the two progressive waves colliding and forming a stationary wave.

Harmonics

When you play a note on an instrument, you aren't generating just one frequency. Instead, the sound is a result of several frequencies, spread across the audible spectrum, which all contribute to an instrument's timbre (how the instrument sounds). This is easiest to visualise with stringed instruments, but the same applies to wind instruments too.

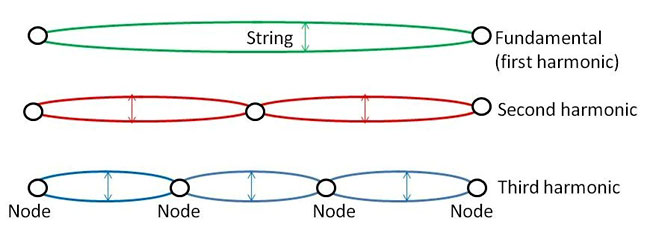

The fundamental (or first) harmonic has a wavelength twice the length of the string, with a node at either end. It contributes the lowest pitch to the overall sound of the note. The second harmonic has a wavelength exactly the length of the string, the third harmonic has a wavelength two-thirds the length of the string, and so on.

An easier way of remembering this pattern is by instead thinking how many wavelengths will fit on the string:

| Harmonic | No. of wavelengths |

| Fundamental/1st | 0.5 |

| 2nd | 1 |

| 3rd | 1.5 |

| 4th | 2 |

And so on.